One of the most senior figures to defect from Somalia’s al-Qaeda-linked militant group al-Shabab has urged his former colleagues to stop targeting civilians and to begin negotiations with the Somali government.

In his first interview with a foreign journalist, Zakariya Ahmed Ismail Hersi – who once had a $3m (£1.9m; €2.7m) bounty from the US government on his head – condemned al-Shabab’s attack on Garissa University College in Kenya in April, where 148 students were killed.

Speaking at a government safe-house in Mogadishu, he described it as “wrong and unlawful” and offered his condolences to the victims and their families.

Inside his heavily guarded residence he tells me the story of his rise through the ranks of the jihadists until the group’s policy of extreme attacks on civilians forced him to flee for his life.

Mr Hersi’s defection – a lengthy process that appears to have begun in 2013, if not before – is now the centrepiece of a new government amnesty initiative designed to convince other militant leaders to follow suit.

“The path became wrong… and I had a tipping point,” he said in fluent English.

‘They’re trying to kill me’

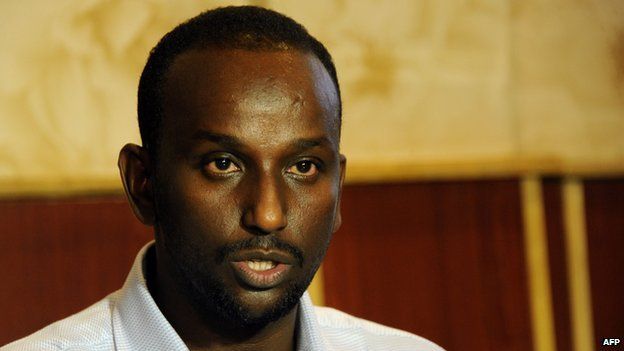

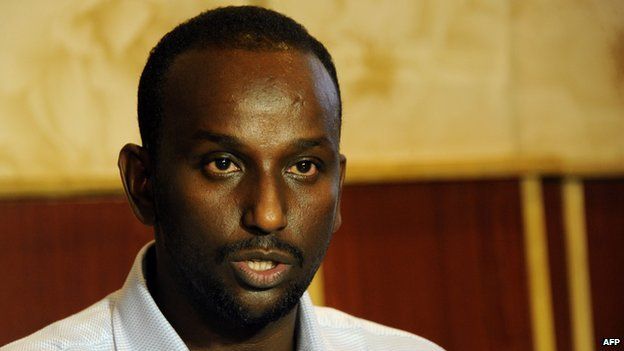

Mr Hersi – widely known as Zaki – is a youthful, slim 33-year-old with a neatly trimmed beard and moustache.

Wearing a new, Western-style checked shirt he struck me as proud, thoughtful, and extremely careful in the way he sought to present himself as a devout Somali patriot, who had been trapped inside a militant group that had lost its way.

“Now they’re trying to kill me,” he said of his former colleagues in al-Shabab, which explains the tight security at the safe house where a soldier manned a makeshift watchtower and two more guarded the gate.

After months of debriefing, Mr Hersi is now technically a free man, with access to a mobile phone. “I’m on social media, Twitter and Facebook,” he volunteered.

Aiding defectors

I asked him if he had been in touch with people in al-Shabab, and indeed whether it was a condition of his defection that he try to persuade others to swap sides.

“It’s not a condition. But if I got a [phone] connection I will try to encourage them definitely,” he said, praising his treatment at the hands of Somalia’s intelligence services.

“They treated me very nice. Welcomed me in a very good way and I thank the government for that welcome.”

Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud says Mr Hersi’s defection – the third of its kind in recent times – is the result of growing military pressure on al-Shabab.

“There was no defection two or even one year back. They were not fighting among themselves or killing some of their own leaders. The reason we have some high value targets defecting today is because of pressure… from the Somali National Army and Amisom (the African Union peacekeeping force) and in the air by our international partners,” President Mohamud told me.

He was referring to the US drone strikes which he praised for their “minimal collateral effect – surgically targeted to al-Shabab’s high level leadership”.

Stopping al-Shabab

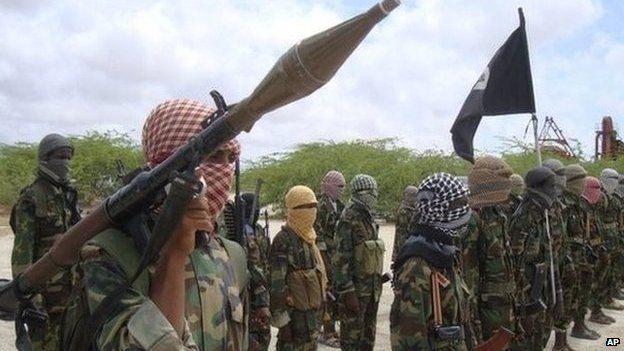

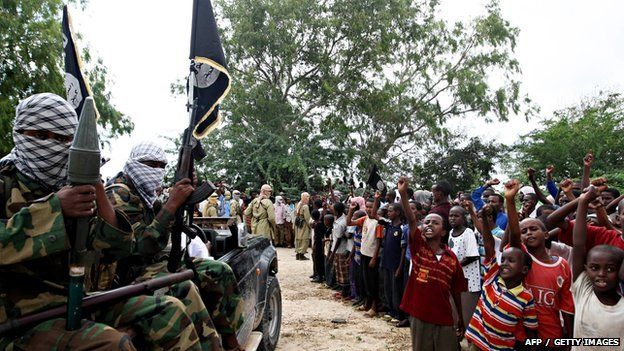

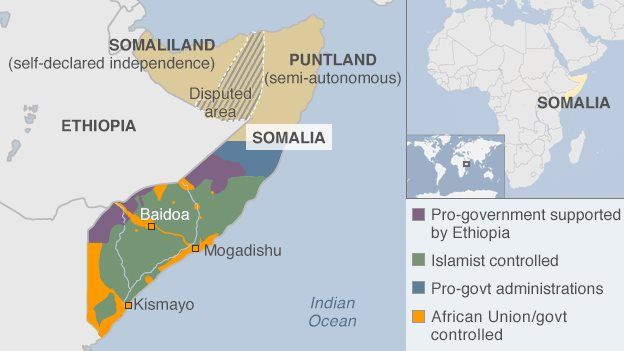

President Mohamud acknowledged that al-Shabab remains a powerful force inside Somalia – as shown by its continuing attacks in Mogadishu – and that the government’s own weaknesses were “considerable”.

But he said the government was improving its approach to tackling the group, citing a recent attack on the education ministry in the city that was quickly contained by security forces.

“That would never have ended like that in the past. Someone who wants to die – you hardly know how to stop them.

“But we succeeded to minimize the impact. Every single attack al-Shabab makes, the casualties are less, because we are learning. The Somali people are learning and are alerting the security forces,” he said.

Mr Hersi told me he had given the government “very good advice” about how to defeat al-Shabab. He declined to give details but said he thinks “they’re doing the right things”.

However, he did suggest that a few amnesties and a few drone strikes would not be enough, and that “a complete strategy” was required to tackle “the thousands still inside the organisation”.

‘We were liberators’

Mr Hersi joined the militant group in 2007. He had been studying economics in Pakistan and came home for a holiday to get married.

Neighbouring Ethiopia had recently invaded Somalia, with implicit US support, to oust the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). The conservative religious group had succeeded in bringing much needed stability to Mogadishu, but it included figures linked to international terrorism.

The ICU was quickly eclipsed by its increasingly militant armed wing, al-Shabab.

“Our aim was to liberate the country,” said Mr Hersi, proudly comparing the fight against Ethiopia to Britain’s war against Nazi Germany.

“Did Churchill waste his time? We were doing just what they were doing,” he said forcefully.

Fleeing for his life

Mr Hersi appears to have risen quickly in the ranks.

“As an educated person my job was in a leading position. I was running some offices, like media, like regional affairs. In 2010 I joined military intelligence,” he says.

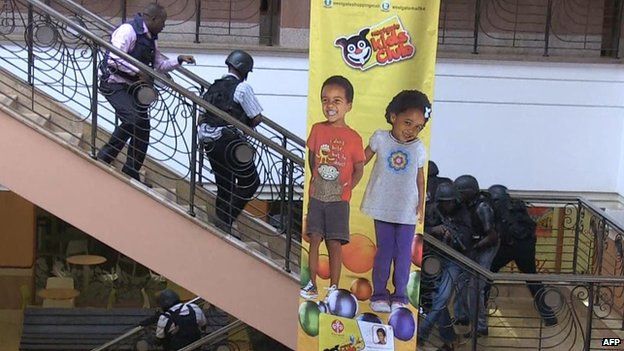

Mr Hersi eventually ran that group, but vehemently denied that he also led al-Shabab’s notorious Amniyat – the intelligence service responsible for planning atrocities like the attack in Kenya on Nairobi’s Westgate Mall in September 2013.

“Such operations were not in the duty of the military. It was Aminyat’s operation, not ours. I was not in al-Shabab at that time. I left in June 2013,” he said.

It was a growing sense of disillusionment with the group’s direction that Mr Hersi says pushed him towards defecting.

Forming an alliance with al-Qaeda “was a very big mistake. Our duty at that time was only to liberate Somalia – our interests were local.” He added that it had a huge effect and diverted al-Shabab from is purpose.

“Now it turns to terror acts, organised crime… we were against all that. In late 2010/2011 there was a lot of misunderstanding within the core leadership of al-Shabab… in terms of these terrorism events.

“When we failed to get an agreement with [the group’s former leader, killed by a US drone strike in 2014, Ahmed Abdi] Godane and his inner circle, they started to silence all opposition.

“They started arresting and killing… some of my colleagues have been killed; some are still in prison,” he said, insisting that he had finally abandoned al-Shabab in order to save his own life.

Al-Shabab recruiting in Kenyan towns

Lying?

I suggested to Mr Hersi that he was lying about his past, neatly tailoring his curriculum vitae, and had only jumped ship because he had lost a power struggle within al-Shabab.

His response illustrated the moral and political tight rope he is now walking as he seeks to win some sort of public acceptance outside al-Shabab.

On the one hand, Mr Hersi seemed stung by the idea that he had lost power within the organisation.

“When I was leaving, I was in a fully powerful position. I decided on my own choice,” he said tetchily, insisting he had defected with only one precondition, that he not be harmed, or handed over “to some other foreign countries”.

On the other hand, Mr Hersi sought to present himself as an isolated figure in a highly bureaucratic system that prevented him from knowing about, or having any responsibility for, al-Shabab’s brutal activities.

“I haven’t seen such an event,” he said of the group’s frequent public stonings and beheadings.

“Most of the time I was in civil positions… a normal job,” he later insisted. “The wrong activities came from other persons. But me personally, I believe I didn’t commit any wrong thing.

“Such an act [like the Garissa attack] is not discussed in an open way. It is between the Amniyat and the Emir [leader] only.

“This is the nature of the organisation. You have to be with your duty only. You can’t ask anything about what they’re doing. Otherwise they will suspect you – so you have to save your life,” Mr Hersi said.

Some may find this hard to believe. But in public, at least, Somalia’s intelligence services are hiding any scepticism.

“I think that’s the typical story of many, many former al-Shabab members, whether at a senior level or low level. We understand that’s the situation [with Mr Hersi],” said senior government counter-terrorism advisor Hussein Sheikh Ali.

“Of course he’s been part of that organisation at the decision-making level, but we don’t have any evidence that he was part of any particular [terror] incident,” he said.

Further defections?

Mr Ali declined to reveal how many senior al-Shabab leaders were now in talks with the government about defecting, but credible sources suggest about 10 of the top 50 figures may have made some sort of contact.

“We cannot kill every member, or put every member in prison. The plan is to offer them a chance to leave – to give them an exit route where they can change their mind.

“So we must persuade them that they must come to a normal life. We’re talking about senior levels – a very few at the decision-making level,” said Mr Ali.

An earlier defection – of former leader Sheikh Hassan Dahir Aweys – was widely considered to have been badly handled, with the elderly man shown publicly in handcuffs.

“Overall they want assurances that when they come over they will receive fair treatment and they will be able to live a normal life,” said Mr Ali, giving a flavour of the sort of private discussions he has been having with al-Shabab leaders who appear to be following Mr Hersi’s case with great interest.

“We want to keep him secure and help him to go back to a normal life. He’s a very known figure with al-Shabab’s leadership and overall within the organisation, and he is committed to talk to those members that he left… hopefully on a personal level.

“So this is a domino effect where all those members who left the organisation will tell the real story here so those remaining can make up their mind…. that coming over is not something they’re going to regret. I’m sure they’re watching very closely,” said Mr Ali.

Domino defections?

Somalia’s government, which is coordinating its defectors programme closely with the international community, is combining the carrot of an amnesty with the stick of its own new “wanted” list, with 13 names, and a combined bounty of at least $1.3m (€1.1m, £800,000).

Will there be a domino effect? Some observers are sceptical.

“I’m not persuaded this was the coup the government and its partners tried to portray it as,” said Somalia analyst Matt Bryden.

“These public recantations are given a lot of importance. They’re noteworthy, but there’s only so much value to be had in parading defectors or prisoners in this way,

“It’s clear these decapitations have not seriously degraded the organisation’s capability,” he added, pointing to the continued attacks in both Somalia and Kenya.

Although Somalia’s government says some 80% of the country is now under its control – a dramatic shift from just 3 or 4 years ago – the organisation clearly remains a highly influential and powerful force.

There is growing concern about the extent to which al-Shabab has now infiltrated Kenya, as well as real fears of escalating violence in Jubaland, the border area inside Somalia where Kenya’s military has sought to carve out a buffer zone.

Meanwhile, Mr Hersi waits in his safe-house.

The afternoon I met him he seemed generally relaxed, often breaking into a smile, and claimed to be busy planning his own “bright future… saving the country”.

There is talk of a cooling-off period, perhaps studying abroad, but Mr Hersi did not hide his own political ambitions.

“I haven’t decided yet, but it seems so,” he said, when I asked if he wanted to run for office in Somalia.

As for his agenda – he said he had no interest in al-Shabab’s professed commitment to building a regional Islamic caliphate. “We have Sharia law here [already]. We have to make further developments… in security, education. To improve the livelihoods of the people,” he said.

‘A normal life’

In the gloomy, but spacious house he now shares with his own personal bodyguards and an assistant, he showed me a small collection of books.

I spotted Islam and Democracy, The Black Man’s Burden and Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point.

“I live a normal life,” he said with a short, ambiguous laugh. His wife and children are, he said, also being kept somewhere secure in Mogadishu.

I asked him if he felt joining al-Shabab had been a mistake, whether he was weighed down by regret. No, he insisted.

So did he really think that people in Mogadishu – a city now slowly emerging from decades of anarchy and conflict – might one day vote for him?

“The vote depends on your agenda. And how you prepare it,” he said, in confident tones of a man shrugging off one mission, and embarking on a new one.

Original source: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-32791713