Documents reveal Britain made secret deal to defend Kenya in case of invasion by Somalia

Britain made a secret undertaking in 1967 to defend Kenya in case of an invasion by Somalia, declassified documents recently released from the Prime Minister’s office in London reveal.

The deal, known as the “Bamburi Understanding”, was a reassurance following a non-committal statement made by Mr Duncan Sandys, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, in 1964.

Without making any concrete commitment, Mr Sandys had told Kenya’s new government that in case of an attack by Somalia, it was probable that Britain would intervene.

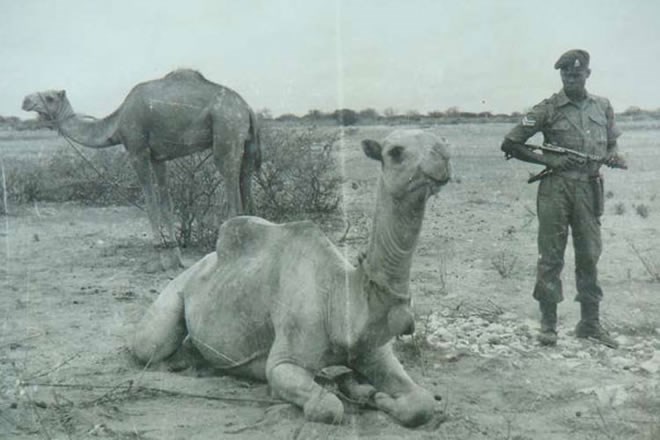

Somalia, which was then considered to have one of the region’s most powerful armies equipped with sophisticated Soviet-made weapons, had threatened to annex the north eastern part of Kenya in pursuit of its Greater Somalia policy. President Jomo Kenyatta’s administration had since independence in 1963 been grappling with a secessionist conflict in the north east, known as the Shifta War, that was supported by Somalia. Indeed, Somali Prime minister Muhammad Egal had told British MPs in 1962 of the intention to unite all territories occupied by Somalis in Kenya and Ethiopia

When Somalia’s aggressive action seemed likely to lead to an invasion of Kenya in 1966, President Kenyatta quickly dispatched Attorney-General Charles Njonjo and Agriculture Minister Bruce Mckenzie to London to pressure the British government to not only give reassurances of protecting Kenya but also provide more sophisticated equipment.

DECLASSIFIED DOCUMENTS

According to the declassified documents, although the British government turned down the request for arms terming it “unrealistic”, Prime Minister Harold Wilson, in a private message to President Kenyatta, committed to consider protecting Kenya from Somalia’s aggression.

This private message marked “secret” was what came to be known as the “Bamburi Understanding”.

“If Kenya were the victim of outright aggression by Somalia, the British government would give the situation most urgent consideration. While the British government cannot in advance give the Kenya Government any assurance of automatic assistance, the possibility of Britain giving the Kenyans assistance in the event of organised and unprovoked armed attack by Somalia is not precluded,” the message read.

Nine months after the “Bamburi Understanding”, a key diplomatic milestone was achieved when mediation spearheaded by Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda led to the signing of the Arusha Memorandum between Kenya and Somalia to end border hostilities.

But the Somalia government, which had signed the Arusha Memorandum, was overthrown and replaced by a military junta led by General Siad Barre in 1969.

This resulted in apprehension with senior Kenyan officials fearing that General Barre was more likely to revive and pursue the Greater Somalia ambitions actively.

ANOTHER BLOW

As if that was not enough, Kenya suffered another blow when the British Labour administration, which had made defence commitments through the “Bamburi Understanding,” was replaced by the Conservatives under Prime Minister Edward Heath in June 1970, creating further anxiety.

This sudden turn of events forced President Kenyatta to send Mr Njonjo and Mr Mckenzie with a private letter seeking reaffirmation from the new British Prime Minister on maintaining the security understanding.

“I have asked them (Mr Njonjo and Mr Mckenzie) to discuss with you what we now here call the Bamburi Understanding. I hope that you will kindly discuss this matter with my ministers who have my authority to do so. I am keen that the understanding should be continued with your government,” read the letter dated August 30, 1970 and signed by President Kenyatta.

Mr Mckenzie, who was on sick leave in Britain, booked the appointment with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to deliver the letter to Number 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister’s residence in London.

The appointment was confirmed for September 8, 1970 at 11 am.

A BRIEF

Four days before the meeting, a brief was forwarded to Prime Minister Heath by the FCO warning that President Kenyatta was going to be unhappy if Britain refused to carry on with the “Bamburi Understanding”. The brief argued that Kenyans were among the most moderate on the “Arms for South Africa” issue — in reference to Britain selling weapons to the Apartheid government despite widespread opposition from many African countries — making it crucial for the new British government not to antagonise them.

In the brief that was written in the context of the Cold War between the Western and Eastern blocs, the Prime Minister was also advised to raise British concerns with the Kenyan emissaries about the Soviet Union’s attempts to penetrate East Africa. There was also to be the clincher that the former colonial masters were willing to co-operate on the defence problem so long as British soldiers were allowed continued access to Kenyan military facilities.

Biographical notes annexed to the brief further give insights on how the British viewed the two Kenyan ministers.

Mr Njonjo was described as one of the closest and friendliest ministers to the British High Commission in Nairobi. Although he lacked political will or the grassroots support to win the presidency, he was viewed as a leading architect in the Kenyatta succession.

ALSO INFORMED

The Prime Minister’s office was also informed that Mr Njonjo loved to have mid-morning tea with hot milk but there should also be Indian tea with cold milk and Chinese tea with lemon.

In their brief, the British officials, however, sneered that Mr Njonjo’s undoing in the Kenyan political context was that he was “obviously presenting a very Western image politically and personally even to the extent of a black jacket and striped trousers and a rose buttonhole daily”.

On his part, Mr Mckenzie was described as a “dynamo of the Kenya Government machine” whose influence extended far beyond his Agriculture ministry. He was also described as a member of President Kenyatta’s inner circle who had gained the respect of the Kenyan European community with whom he previously had a difficult relationship.

“But he always puts Kenya’s interest first. Tries to be genuinely non-aligned when it serves Kenya’s interests,” added the FCO brief.

However, Kenya had a special request to make: It wanted Mr Njonjo’s presence in London and the existence of the “Bamburi Understanding” kept secret.

Not even the Kenyan High Commissioner in London was supposed to know about the mission, according to a confidential letter from a Mr McClauney of the FCO to the Prime Minister’s office.

STATEMENT RELEASED

Mr McClauney, however, advised that if Mr Njonjo’s visit leaked, a statement should be released that he had brought a personal message from President Kenyatta and that it was not the practice to disclose the contents of such messages. And if the media assumed that the subject of the meeting was selling arms to South Africa, then this assumption should be allowed to stand.

The secrecy of the meeting was emphasised to Prime Minister Heath by the British Secretary of State: “While I understand that you wish in general for publicity to be given to your discussion with African and other Commonwealth leaders, we feel that in this case it would be right to respect the Kenyan request, in so far as we can do so without appearing disingenuous.”

Arrangements were, therefore, made for Mr Njonjo and Mr Mckenzie to enter the British Prime Minister’s office through the Cabinet office instead of the main entrance to avoid public attention.

During the meeting, the declassified documents indicate, Mr Mckenzie pointed out the importance of reaffirming the “Bamburi Understanding”. In return, the British forces would be free to continue using Nairobi Airport, the Mombasa port as well as military training facilities in Kenya. They also had great interest in retaining the British special forces who were training Kenya’s General Service Unit commandos and the Special Branch. The visiting ministers linked the work the British special forces were doing in Kenya to the security arrangement against Somali’s aggression.

NOTHING WRONG

In response, the British Prime Minister said that in principle he saw nothing wrong in reaffirming the “Bamburi Understanding” but promised to have the issue fully considered and a reply sent to President Kenyatta.

Prime Minister Heath also promised to consider the request to have the special forces remain in Kenya and pointed out his government did not wish to reduce the use of Kenyan military facilities by British troops. He, however, warned that British military resources were stretched at the time because of instability in Northern Ireland.

But the discussions went beyond defence matters, according to the documents. Mr Njonjo and Mr Mckenzie also discussed development and diplomatic issues. For example, they said that while they appreciated Britain’s support, there were problems with the administration of the aid programme since conditions laid down by the previous Labour government were inflexible, projects were delayed and important payments also held up longer than necessary.

Mr Mckenzie suggested it would be helpful if Kenya’s Finance minister Mwai Kibaki, who was at an International Monetary Fund meeting in Copenhagen, passed through London to meet the British minister for Overseas Development.

SPECIAL INTEREST

The two also felt that Kenya no longer enjoyed close contacts with British government officials and urged Prime Minister Heath to ask one of his junior ministers to take a special interest in Africa and get to know the continent’s leaders personally.

Following the meeting, British officials embarked on drafting the Prime Minister’s reply. But they also secretly noted Mr Mckenzie’s and Mr Njonjo’s ignorance on the “Bamburi Understanding” for linking it to the presence of British special forces and access to Kenyan military facilities.

While the arrangement for British forces to use Kenyan military facilities, airports and harbours was agreed upon at independence with Mr Sandys, who was the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, and the training of the GSU commandoes came into existence in December 1964, the “Bamburi Understanding” was in January 1967.

But British Foreign Secretary Sir Alec Douglas-Home did not think it was worth getting into an argument on the three issues in the Prime Minister’s letter to President Kenyatta.

IN EXISTENCE

As late as May 1981, the agreement was still in existence, according to a brief prepared for Margaret Thatcher, the first female British Prime minister (1979-1990), when she met Kenya’s then Foreign Minister Robert Ouko in London.

“Kenya has our friendship/support. Kenya policy to stand on her own feet militarily is right. We will continue to help Kenya absorb new equipment,” said the brief.

It added that in case Somali attacked Kenya “UK would give all help it could, but it is unlikely our response could include commitment of combat troops. Nor indeed do we suppose that Kenya would wish for this.”

Ironically, despite the fears in the 1960s, it was the Kenyan Defence Forces that would go into Somalia decades later, in October 2011, to pursue al-Shabaab terrorists. The Kenyan forces are now part of the African Union Mission in Somalia that is trying to restore security in the country that has been grappling with civil war since the collapse of the Barre regime in 1991.